Last December I implemented persistent identification. Not just the technology, but—more importantly—the policy meant to give users enough confidence to refer to our links without hesitation. I wrote a blog about that: "Names That Last: on persistent identifiers without the delusion of eternity". In it, I argued that persistence is not the same as “having a Handle or an ARK”—and that some organisations, such as startups, may have to do without, because these systems often come with substantial conditions.

That last part turned out to be an assumption. After finishing that blog and delivering the implementation, I decided to put it to the test and apply for an ARK.

Is the coffee and cake arranged?

Persistence is all about a promise: can others trust that you will keep your promise to make information available?

The elephant in the persistence room is trust in your PIDs and resolver after the proverbial curtain has fallen.

And for a startup, that risk is not small. You do not solve that with technology.

“Persistent” therefore means transferable, not eternal.

You promise to set things up so that they do not depend on you.

You promise that the meaning of identifiers is documented.

You promise that the mapping from PID to current addresses is not locked away in an obscure database, but exists as an open and usable source.

What you do not promise is that you will exist forever and keep paying the bills.

Good persistence policy extends beyond the final exit. We quickly think about dissolution: besides coffee and cake, are there agreements with an umbrella organisation, an archive, or an institution such as DANS?

But the danger of transience is much closer. Nothing turns out to be as temporary as an organisation’s name—and therefore its internet domain.

What happens in a merger, a split, a reorganisation, or the management favourite: a “recalibration of strategic goals and identity”?

Can you promise you will always keep old domains online?

That the old resolver will keep redirecting visitors?

Or do you choose a neutral internet address for that reason?

External resolvers

To make the “life after death” promise, platforms such as ARK, Handle, and DOI offer services. Instead of:

https://pid.p-322.com/p322/blog/01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW

you use something like:

https://n2t.net/ark:12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

or

http://hdl.handle.net/10648/35429da7-5297-a382-e063-6df0900a6686

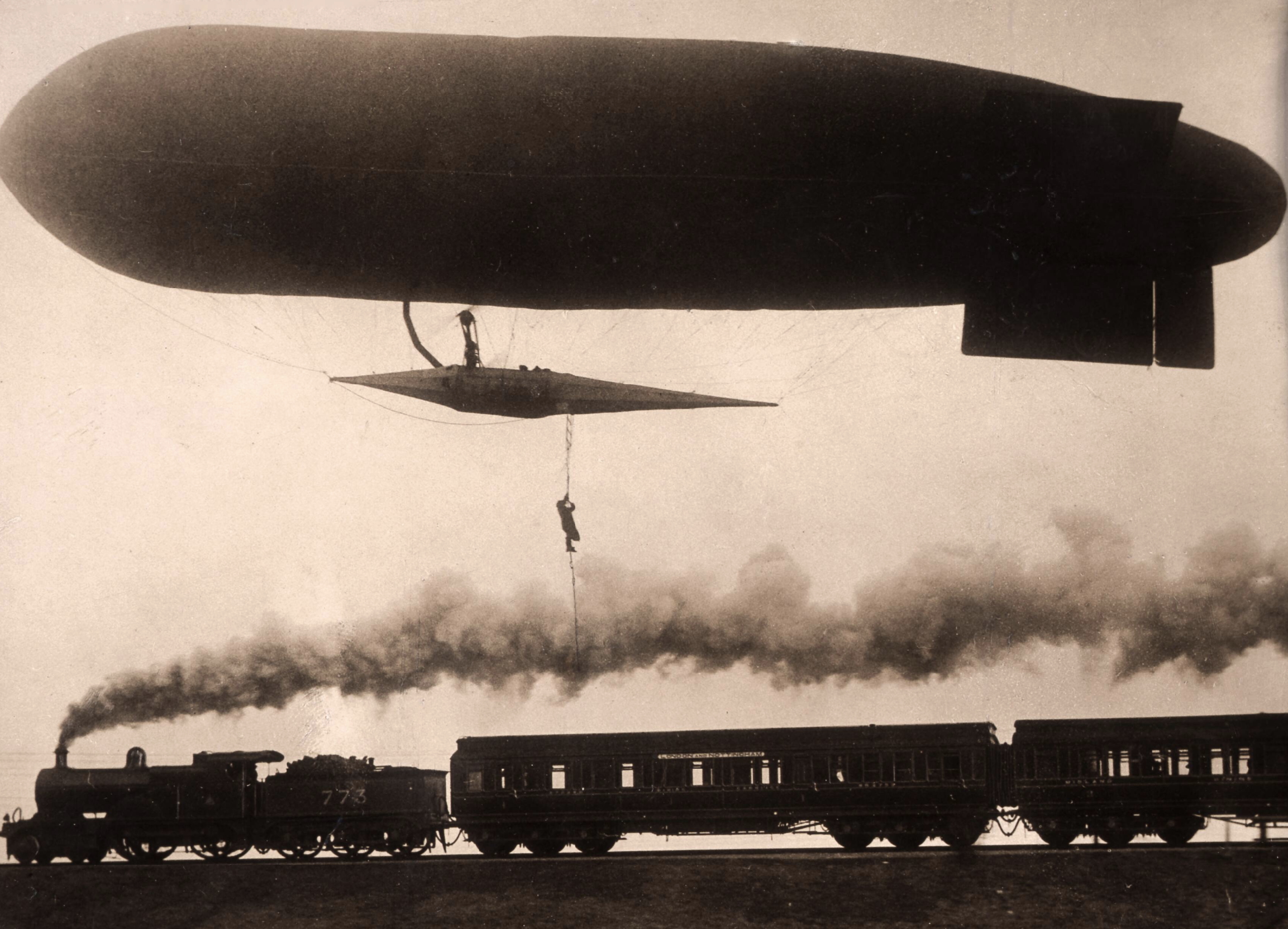

In ARK and Handle addresses, the fragments 12148 and 10648 are the Name Assigning Authority Number (NAAN) and the Handle, respectively. They function as a space—the namespace—for a participating organisation. Handle 10648 belongs to the National Archives of the Netherlands, and everything after it is an identifier for an object from the NA. For example, 35429da7-5297-a382-e063-6df0900a6686 is a photograph of distinguished gentlemen on a platform at the first steam train in Aalsmeer. The Handle resolver redirects the visitor to the image in the photo collection.

That is elegant—but before ARK, Handle, or DOI assigns your organisation such a number, you typically have to meet a range of requirements. I therefore assumed that, as a startup, we would struggle to qualify. But you lose nothing by trying, and you might get a yes: I decided to make a choice and see how far I would get.

If they all reject us, the application process will still be instructive. And to guarantee an outcome, I also included PURL. You can always fall back to that.

This is not Pepsi versus Coke

In the sector, you hear people talk about Handle, DOI, and ARK as if it were Pepsi versus Coke: a matter of preference, price, or taste.

That is uncomfortable, because they are not easily comparable.

They do very different things. Not better or worse—different. The wrong argument for making a choice is therefore: ARK is free.

At the time, I still thought the choice would mainly be a technical and organisational trade-off. Only later did it become clear that this decision forced me to answer a far harder question.

What happens when the same infrastructure has to serve archiving, scholarly citation, and marketing at the same time? But let me not get ahead of myself and first lay out the different systems side by side—not to compare them by taste or price, but to make visible what problem each is trying to solve, and what it very explicitly does not solve. Only from that distinction does it become clear why some combinations chafe, and others create breathing room.

Handle: technology with a central registry

Handle is primarily a technical protocol. It requires you to resolve your PIDs via a central registry to the location where the data lives.

That registry is maintained by the non-profit research organisation the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI).

Handle imposes only technical requirements on participants’ persistence promise. In my previous blog I explained how resolving a P-322 PID to the “real” location of the data currently includes the address https://pid.p-322.com as an intermediate step. If you use Handle to map PIDs to data, that intermediate step is no longer needed. Resolution goes via the central registry directly to your local addresses. Do those change? Then you update the registry at CNRI.

A Handle implementation therefore removes one hop and the cost of running your own server solution. For that, the non-profit charges $50 for registration and an annual service contribution of $50.

That could easily be cheaper than a “free” ARK for which you still have to operate and maintain your own solution.

Digital Object Identifiers (DOI): assurance via contract and metadata

DOI was created because Handle is mainly a technical answer to an institutional problem. In many respects, a DOI is everything that Handle is not—hence why they complement each other so well.

A DOI is, above all, a legal/organisational solution.

You enter into a contract with a provider—a Registration Agency (RA)—that forces you to implement a set of policy measures. DOI is a governance structure. You pay money for the privilege of being compelled to get your policy in order. In return, you can request PIDs whose persistence is underwritten by your RA.

That may sound a little sour, but it brings your persistence promise as close as possible to the technically guaranteed persistence that I argued last week does not exist. With many RAs, you pay an annual fee of a few hundred dollars and, in addition, a fee per PID.

What you buy with that money is risk reduction: fewer broken links, and less reputational and continuity damage. With a DOI, you can—practically speaking—assume that the PID will keep working even after reorganisations, platform migrations, and staff changes.

On top of that, DOI PIDs must meet mandatory metadata requirements that are validated by the RA. That way, everyone can trust that authors are who they claim to be, affiliations are correct, the licence is established, and a stack of other assurances is in place. The RA also takes care of automated metadata distribution to third parties.

As a result, a DOI grants academic legitimacy. DOI PIDs are first-class citizens in scholarly citation indexes, research information systems, and many funding and evaluation frameworks.

With Handle, you pay for a number and the ability to manage persistence yourself via a central registry. With DOI, you pay for institutional assurance: the guarantee that you will do it. If you fail to comply, the RA may ultimately do it for you—so the ecosystem remains persistent.

How does DOI work technically? Well… it does so via a Handle implementation.

That is why DOI can be everything that Handle is not. DOI complements Handle, but it does not replace it.

Archival Resource Key (ARK): redirection with maximum freedom

Although ARK resembles Handle, it is more a design principle than a technical solution. In ARK, your number is a NAAN. With that NAAN, you gain access to the global N2T resolvers (Name-to-Thing) that recognise these numbers and forward traffic to you.

So the only thing ARK does is forward traffic to your local resolver. From that point on, you are on your own.

To introduce some guarantees, the ARK Alliance expects you to register a test PID that allows them to check whether your resolver works. But there is no institutional assurance attached. For the vast majority of organisations with an ARK NAAN, even that test PID is missing. If we descend further into the ARK specifications (2008), we find additional formal rules intended to strengthen the promise:

ark:<NAAN>/<local pid> resolves to the data.

ark:<NAAN>/<local pid>? resolves to metadata about the data.

ark:<NAAN>/<local pid>?? resolves to the organisation’s commitment statement describing its persistence policy.

I do not know a single organisation that actually does this.

Since 2022, there has been an update to these requirements, and it even looks as if the ARK community has partially conceded the point:

"ARK resolvers must support the "?info" inflection for requesting metadata. Older versions of this specification distinguished between two minimal inflections: '?' (brief metadata) and '??' (more metadata). While these older inflections are still reserved, because they have proven hard to recognize in some environments, supporting them is optional."

But even that ?info inflection is missing almost everywhere.

In practice, ARK differs from Handle mainly because it is less centralised and is less strict about its limited requirements. With ARK, you therefore carry substantial responsibility yourself.

And that is precisely why ARK is by far the most flexible option.

Once you have made the institutional commitment to persistent identifiers, formulated appropriate policy, and implemented the technology, ARK is a low-threshold way to finish the job. The ARK N2T server in front of your own resolver signals to users that links—even if your organisation and internet domain disappear—still resolve to a meaningful place.

You can achieve something similar with Handle, but it requires more work.

The difference ultimately comes down to this: do you want the flexibility of your own solution? Or do you choose a central registry so you do not have to run your own server?

Persistent URL (PURL): minimal promise, maximum simplicity

If DOI is the heavyweight of the persistence family, and ARK the lightweight, then I also want to mention the smallest sibling: PURL. ARK at least aims to support certain guarded guarantees. PURL does not.

PURL—like Handle—is a central registry running as a single service. The system was developed by OCLC, a library software vendor, and is now operated by The Internet Archive. With PURL you can redirect purl.org addresses to a URL. Where ARK has you register a NAAN, PURL lets you choose an as-yet-unused string and requires no contract. It discards the entire legal-institutional assurance layer.

PURL redirects your user to another address. Nothing more, nothing less.

Is it fair to call that “persistent”?

I actually think it is. Because just as with ARK, Handle, and DOI, you still have to do something yourself. The difference is only how strongly that “doing it yourself” is enforced.

PURL provides no more technically guaranteed persistence than any other external party.

But, like all the other options, it gives you the possibility to act persistently.

In my previous blog I explained that you can even act persistently using an arbitrary address on your own domain—you do not need a resolver for that. Ultimately the question is: have you taken enough measures to convince others to use your persistent links?

PURL fits into that list of possible measures. You are simply entirely on your own as an organisation. If you can manage that—and users believe you—then a PURL-based setup can be persistent.

What if you want to be independent of the US?

To make things a little more complex: for any platform choice today, it is healthy to ask how dependent you are on the US. Unfortunately, I do not have good news.

Handle is run by a solid non-profit (CNRI) in the United States. DOI is governed by the International DOI Foundation (IDF): a non-profit… in the United States. The IDF oversees Registration Agencies around the world. Two major RAs are DataCite and mEDRA, based in Germany and Italy respectively, and therefore operating under European law. I cannot say with confidence how (in)dependent they are from the foundation in the US; there are contractual arrangements in place.

The ARK Alliance has no formal organisation and is an open international community. This commons was originally set up by the California Digital Library (CDL), but it is not a legal part of CDL. It is not a subsidiary, a foundation, or any other legal entity. ARK is not a system with an owner. It is an agreement under which you take responsibility yourself.

That sounds beautiful and idealistic. But in practice, someone still assigns and registers NAANs and runs the N2T servers.

That “someone” is still CDL in the United States. There is no European fallback for ARK, even though the NAAN registrations are published on GitHub. That may be less problematic because, even without CDL, calling https://pid.p-322.com/ark:<NAAN>/<local pid> would still work—but for institutional authority and the N2T resolver hop, ARK is just as dependent on the US as Handle, and probably DOI.

Then there is PURL. OCLC no longer plays a role, but purl.org is operated by The Internet Archive. It starts to sound like a stuck record: that too is a non-profit organisation in the United States.

In short: there seems to be room for a European solution—preferably one where we do not start from scratch, but make agreements with the Americans.

And then: choosing

Up to this point it was theory; now I actually had to choose.

DOI was the first to drop out. I do not see us writing research papers independently, at scale, any time soon. Nor do we aim for an institutional position within academia. If we do want to publish, there are plenty of partners we can collaborate with. As a startup, I also suspect we would not be able to implement the required policy effectively—but I did not investigate that in detail.

That left Handle, ARK, and PURL.

All three work technically. But what does not help Handle is that I have a healthy aversion to centralised solutions. That is a personal preference; there are perfectly sound arguments for choosing a central registry. It depends on your organisation, your persistence policy, and your technical architecture.

For P-322, I had just built my own resolver (https://pid.p-322.com). In all honesty, I was not enthusiastic about sinking it again and replacing it with the central Handle registry. That would also make my previous blog immediately outdated.

The minimalist character of PURL is highly attractive. As technical solutions, ARK and PURL sit fairly close to one another. But PURL does not appear in the guidance of the Netwerk Digitaal Erfgoed. That means you would constantly have to do extra work to explain that your infrastructure is genuinely set up for persistence.

With ARK, Handle, and DOI, you do not.

If the goal is to build trust in your links, and the digital heritage community happens to trust PURL less? Then we choose ARK first, and only fall back to PURL if ARK does not work out. It probably would have been PURL if I had only had to weigh technical reasons.

But first: ARK.

The ARK application process

For the application, you need to arrange two things.

First, the P-322 resolver must not only be able to redirect:

https://pid.p-322.com/p322:blog:01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW

to the right address, but also:

https://pid.p-322.com/ark:<ARBITRARY_NAAN>/p322:blog:01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW.

That was done quickly. It may look complicated, but the software was written to redirect things. If it works for one pattern, it will work for another. For the application, it does not matter which NAAN you forward—because you do not have the number yet.

Next, I had to create a PID that points to a service page where ARK can periodically check whether the P-322 resolver is still working.

For that we used p322:status:servicestatus.

Via:

https://pid.p-322.com/ark:<ARBITRARY_NAAN>/p322:status:servicestatus

you are redirected to:

https://p-322.com/status/persistency/

which proves the implementation.

Once you have arranged that, applying for an ARK NAAN turns out to be a simple and fast process. You fill out the form on the ARK Alliance website. They promise to respond within two working days.

I applied for the NAAN on Friday 19 December 2025—many people’s last working day of the year. To my surprise, I received confirmation of our registration on the Monday morning after, including the NAAN: 48229. I have to admit I did not expect that.

Trains of redirects

So P-322 PIDs now work as a train:

https://n2t.net/ark:48229/p322:blog:01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW

is an external location that does not depend on our continued existence, nor on the internet domain p-322.com. If the curtain ever falls, we will send you from here to the P-322 Authoritative External Resolver Repository that I introduced in the previous blog. But while everything is fine, this link pushes the user to:

https://pid.p-322.com/ark:48229/p322:blog:01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW

That resolver then does what it has always done: it looks up p322:blog:01J6E8F3PFQ2H9R7M4K8V1CW in our own registry and automatically redirects you to:

https://p-322.com/en/posts/20251211-outside-the-dataset-within-the-community-enrichments-as-nanopublications/

If we restructure the website next week, we update our registry to the new location. The PID does not change.

And that is precisely the point of persistent identification.

This works for all internet traffic—whether you are a human referencing a blog, or a machine that needs to find specific data at a stable address.

At that point the architecture seemed complete.

Until I realised that we were using another hidden resolver—one with a different purpose and a different time horizon.

The communications department’s secret

Startups and heritage institutions alike: we are all busy communicating online. And then it is useful to analyse the attention that communication draws to your website. We give this exciting names like “redirect services” or “link resolution”. We do it with short fragments like CvNg8x, which we append to a web address and then leave in very specific places.

P-322 uses a so-called go-link for that—for example https://go.p-322.com/CvNg8x. We put it in a LinkedIn post that points people to a blog. The server go.p-322.com looks up CvNg8x and appends standardised tracking parameters such as utm_campaign, utm_medium, and utm_source. That allows communications colleagues to track—precisely and anonymously—how often users click from LinkedIn to a blog during a campaign.

A go-link is therefore not an identifier, but a measurement instrument with short-term memory.

But wait… a piece of software that maps an identifier to the actual current address? That does sound familiar. And indeed: the technology is also a resolver and works in exactly the same way as a PID. It redirects the visitor to https://p-322.com/nl/posts/20251211-buiten-dataset-binnen-gemeenschap-verrijkingen-als-nanopublicaties.

A second resolver, then—but with a radically different purpose.

Go lives on the timescale of a campaign, with the transience of a mayfly. PIDs are meant for the long haul: citation, archiving, and reuse.

Management reality vs technical principles (0–1)

And you can feel it coming: somewhere in the organisation—usually in a management meeting—the temptation arises to merge the two. Why do things twice, after all?

Ugh.

My problem with that is not technical, but principled.

One of the most important lessons in this line of work is that you develop an almost automatic distrust of systems that try to do too much.

Also: analytics is not identity.

If you pull long-term PIDs into your marketing layer, you are asking for trouble.

Not only because durable identity should not depend on the story your organisation tells today, but also because it becomes extremely fragile. Every privacy setting, every ad blocker, every security policy suddenly becomes an existential risk. Browsers are almost designed to distrust or block web analytics. A PID was meant to rise above such temporary frictions.

The resolver trains

That is why we separate everything. The resolver at https://pid.p-322.com concerns itself only with what we publish permanently. It safeguards identifiers that are canonical and citable, and that do not know—and do not need to know—which unrecognisable user is passing through.

The software at https://go.p-322.com is an instrument we can replace tomorrow without regret. It may disappear, change, or be redesigned, without breaking our identity.

You combine the two by chaining them. And the order is not a detail, but a principle. The go-link points to the PID. The PID points to the representation. The flow is clear: go adds context and measurability, the PID protects identity, and the website delivers content. Because each layer has its own job, the whole becomes robust.

Loosely borrowing from Wheeler’s aphorism: “every web problem seems solvable with yet another redirect—until you drown in redirects.”

ARK & Go

So where does the ARK N2T resolver fit? That is a different path, a different train—with a different purpose.

When communications is running a campaign, we publish the go-link in places that have value during that campaign: social media, email footers, and so on. The redirect train then is: go-link → P-322 PID → current web location.

But a PDF report we publish during a campaign, with a reference to data? That gets the PID, never the go-link.

If people choose to use our persistent links on their own, communications plays no role at all. We then provide all the guarantees that come with that. The path becomes: ARK N2T → P-322 PID → current web location.

And that is exactly where the choice for ARK became decisive. With ARK, our own P-322 PID resolver remains the fixed centre of the chains. Both the ARK N2T resolver and the go-links ultimately point there.

If I had chosen Handle, formal PID resolution would have run through the central CNRI registry. Go-links would then either have had to point directly to the website—falling outside the persistence chain—or first go to CNRI, in which case the tracking information would very likely be lost along the way. We do not use Handle, and without a practical test I cannot say that with 100% certainty. But it seems like a complicated story in which your analytics depend on the behaviour of a server outside your control.

ARK, at least, makes it possible to place marketing in front of the PID, without affecting the PID’s identity.

In both trains, the P-322 PID resolver sits at the heart. The paths meet there — and that is exactly the point. It allows us, through our infrastructure, to ensure that the user always ends up in the right place to find the information—without noticing the machinery.

Not everything has to be everything

In the end, this choice was not about ARK, Handle, DOI, or PURL. It was about recognising different promises that deserve different infrastructure. Anyone who tries to compress those promises into one system makes everything more fragile instead of simpler.

Persistent identification requires restraint. Not everything you publish needs to be measurable, and not everything measurable needs to remain permanent. By separating identity from attention, you create room to take both seriously—without letting them undermine each other.

Perhaps that is the core of sustainable digital infrastructure: not striving for systems that can do everything, but for systems that know exactly what they should not do.

And while I was putting this together in the last working week of December, a strange, reassuring simplicity emerged.

You have a durable identity. You have a communications hub. You have internal and external resolvers for mapping and redirection. And an open depot for transferability.

It feels almost boring. As boring as writing a will.

But boring — as I learned last year at the NDE HackaLOD — is often exactly the right feeling for infrastructure that needs to outlive your attention span.